Do you speak European? – Language and Identity in a United Europe

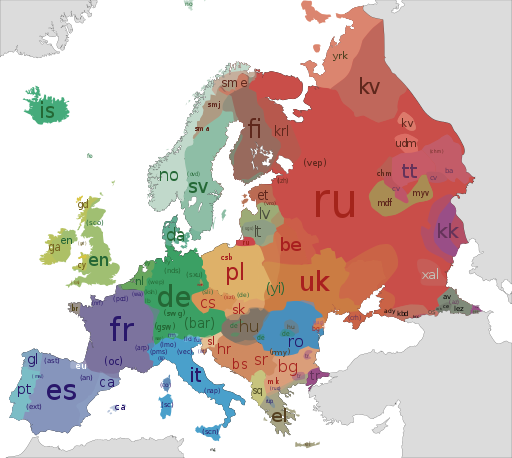

One of the ways in which the magnificent cultural diversity of Europe manifests itself, is in the multiplicity of languages. A vast range of language variants are native to our continent, tens of them are standardized into written form – in at least three different alphabets; many of these serving as the national language for one or more European countries. The European Parliament uses 24 different official languages, which all need interpreters to translate in real time during parliamentary sessions, and translators for all written documentation. More than 9 in 10 Europeans speak a language from the Indo-European language family, most belong to either the Germanic, Romance or Slavic branch. Then there are also smaller Indo-European branches, like Baltic, Celtic or Greek, and languages like Finnish or Maltese, which are part of other families. And finally Basque, which is an isolate with no proven connection to any other language on the planet.

In such a complex linguistic environment, how can we achieve the effective communication that is essential for a strong, united Europe? According to critics, the main obstacle against European integration is the lack of a common European language. According to them, the absence of a unifying language demonstrates that there is no such thing as a ‘European people’. However, a look at other diverse peoples around the world, shows us that multilingualism can go perfectly hand-in-hand with a strong sense of identity. Indians, for example, feel unmistakably Indian; but speak many different languages. The same can be said about Chinese and Indonesians. And one does not even have to look outside of our continent’s borders. Within every European country one finds different subgroups with different regional language variants, sometimes not understandable by their co-nationals from other regions. This does not mean that language is not an important unifying factor for groups of people, but simply that communities are rarely limited to one single language.

Nonetheless, it is true that societies around the world generally have a dominant language, a so-called lingua franca, which helps people of different language backgrounds work and live together. In India that language is Hindi, in Indonesia it is Bahasa Indonesia, and in China it is Mandarin. In Europe, now and in the foreseeable future – whether we like it or not – that language is English. When Europeans with different native languages meet, in the vast majority of cases, they will converse in English. Little more than half the European population speaks English at a conversational level – almost the same percentage of Indians knows Hindi. The percentages of people in China and Indonesia that speak their respective dominant languages are higher, but nowhere near the level of any European nation-state. Even if the UK leaves the European Union – which seems increasingly difficult – English will continue to be Europe’s lingua franca, and, as younger generations inherit our continent, the number of English-speakers will grow exponentially.

While future Europeans will mostly speak English with their peers from other corners of the continent, they will never forget their native tongue. Governments, schools and parents should continue to stimulate – besides teaching children to master their national language – education in one or more major EU languages – German, French, Italian, Spanish, Polish- or any other European language. Moreover, we must continue to value and protect all those hundreds of regional languages that compose the cultural treasure that is our continent.